- Bit Shift Calculator Perform bit shift operations with decimal, hexadecimal, binary and octal numbers. Shift Direction.

- The right-shift operator causes the bit pattern in shift-expression to be shifted to the right by the number of positions specified by additive-expression. For unsigned numbers, the bit positions that have been vacated by the shift operation are zero-filled.

The right shift operator shifts the first operand the specified number of bits to the right. Excess bits shifted off to the right are discarded. Copies of the leftmost bit are shifted in from the left. Since the new leftmost bit has the same value as the previous leftmost bit.

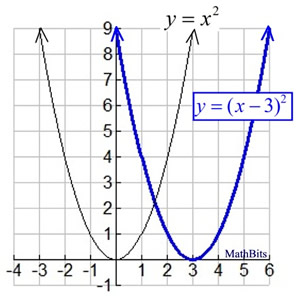

A right shift indicates decreased oxygen affinity of haemoglobin allowing more oxygen to be available to the tissues. A left shift indicates increased oxygen affinity of haemoglobin allowing less oxygen to be available to the tissues. PH: A decrease in the pH shifts the curve to the right, while an increase in pH shifts the curve to the left. Next, let us shift the function along the x-axis. This corresponds to modifying the constant. In this case, a positive value will shift the function to the left, and a negative value will shift it to the right. Again, let us use and, so we get the functions.

It’s a common view these days that the Republican Party has moved decisively “to the right” over the past generation. According to this “rightward shift” narrative, George W. Bush pushed the GOP awayfromthe center, and now, under Donald Trump, the party is indulging its most radicalright-wing tendencies.

The narrative is commonly accepted, but is it correct?

The short answer is “no.” For the past century, limited government has been the defining core of “right wing” ideology and yet it is a well-documented fact that over the last two decades, Republicans have significantly expanded the size and scope of the federal government whenever they have been in power (even outdoing their counterparts on the Democrat side). At the same time, polls show that Republicans have moved to the left on peripheral issues, such as foreign policy and gay rights.

Why, then, does the narrative of a Republican rightward shift persist?

Part of the answer is that both ideological tribes have an incentive to perpetuate it. Those on the right embrace the narrative because it makes them the heroes in a story of conservativetriumph. In this view, courageous conservatives overcame the forces of squishy Rockefeller moderation, ushered in the “Reagan revolution,” and saved the country from the malaise of the 1970s. Those on the left, on the other hand, use the story to delegitimize their opponents by casting Republicans as extremists.

But there’s more to it than just ideological posturing. A number of scholarly studies have also suggested that the party has moved to the right, but each of these studies has serious flaws.

The most common problem is that they manipulatethe meaning of “right wing” ex postto fit the rightward-shift thesis. They look at the direction the GOP moves, declare that direction “right wing” after the fact, and then “conclude” that the party moved to the right. It’s classic circular reasoning.

MS Edge & Pinning Favorites Bar On Right Hand Side Of Screen ...

Yet they can get away with this simply because there is no universal agreement as to what constitutes “right wing.” If the party goes in a more authoritarian, statist direction, they can claim it was a move “to the right.” Conversely, if the party goes in a more libertarian, anti-statist direction, they can also claim it was a move “to the right.”

Free trade used to be considered a pillar of small-government conservatism, and yet when Trump adopted the cause of protectionism, the cry went up that he had moved the Republican Party “to the right” with this “nationalistic” policy. If the next Republican president moves in the opposite direction, the cry will go up that it is a right-wing shift to “free market fundamentalism.” After Republicans turned decisively against the “right wing” foreign policy of George W. Bush, scholars simply switched focus to other issues that better fit their rightward-shift thesis (or even started saying that anti-interventionism had been the “right wing” position all along). We can make the GOP move “rightward” or “leftward” simply by redefining our terms.

Another problem with many of these studies is that they confuse ideological homogeneity with ideological extremism. Scholars often rely on a tool called DW-NOMINATE, which measures roll call votes in Congress to find out, for example, how often Republicans have voted with the conservative side of an issue. Unfortunately, DW-NOMINATE only defines “conservative” in terms of what Republicans are supporting at the time. Yes, Republicans in Congress have become increasingly unified over the past two decades, but voting lockstep for big expansions of government power wouldn’t indicate a shift “to the right” as DW-NOMINATE suggests.

The rightward-shift narrative also persists because of the tendency to mistake rhetoric for reality. It focuses on what Republicans say, rather than on what they do. If the GOP moves right in words, but moves left in deeds, which direction has it really moved? Ever since the rise of talk radio, Fox News, and social media, Republicans have used harsher rhetoric (e.g., “Build the wall!”), but it’s often in service of the same, often moderate, policy views (e.g., enforcing immigration laws).

But it’s not even clear that there has been a rightward shift in Republican language, since these studies often rely on comparative rather than absolute measures of ideology. Slightly fewer Republicans today than in the past believe “the government should do more for the needy,” but this change has occurred even as government anti-poverty spending has risen substantially. This is less evidence for a rightward shift among Republicans and more evidence for a leftward shift in government policy. If the country moves left on an issue, but the Republicans don’t move quite as far left, this is, strangely, taken as evidence that Republicans have moved to the right.

As should be apparent, we can make anyone appear to have moved right or left on a political spectrum simply by manipulating our terms, focusing on rhetoric over reality, or by using comparative instead of absolute measures of ideology, but this only serves to confuse rather than clarify. We would be better served focusing more on what our political parties are actually doing and less on how they fit on a bizarre and ultimately meaningless unidimensional spectrum.

Hyrum Lewis is a professor of history at Brigham Young University-Idaho.

Cached

Right Shift In Neutrophils